The first 4th of July parade I ever participated in was in Round Top, Texas. It was humid and sunny and hot and miserable and one of the most incredible experiences of my life. Little did I know then the significance of that celebration, or about the series of events that had built the streets on which the parade progressed.

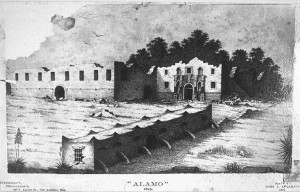

When Texas was still Mexico and Santa Anna’s soldiers and officers alike cringed as they carried out the orders to torture and dismember and exterminate and burn the captured and wounded Texians at the Alamo in Bexar and then again at Goliad, there lived in and around what was then known as the Townsend Settlement on the Old LaBahia Road a group of primarily English settlers. They had entered the country lawfully and had been granted by Stephen F. Austin—and by extension Mexico itself—leagues of land to farm and to use to raise livestock… and to defend.

In just a decade, these Englishmen and women had weaved themselves into the fabric of the countryside, scratching out a life raising corn and tobacco and hunting and living off the land and establishing a church now long gone and a Masonic lodge to ensure their beliefs came to this new world with them. They displaced the few poor remaining and starving Tonkawas and Karankawas that suffered along Cummins Creek out of belief that it was their duty, and they offered stiff-English-upper-lip resistance to the raiding horse-mounted warrior Comanches as the Mexican government had hoped they would.

When the news of the defeat at Bexar and the 500 massacred at Goliad reached the Townsend Settlement, their world changed. The men first took care to pack up their most precious wives and children as best they could, killing and salting the pigs even though the weather was not cold in hopes that it would be enough to feed them clear of the country. And they all left the settlement the same day, the women and children in wagons to the east and the men on horseback to the south to meet up with Sam Houston and the Texian army.

The women and children struggled and survived and died along the muddy road toward the Trinity in flight from the Mexicans and no doubt experienced the worst days of their lives, struggling and starving and eating pork and rabbit and squirrel and even skunk, if they had anything to eat at all. And the men were forced from their mounts by Houston’s orders and they grumbled and went hungry while drilling on foot for what must have seemed like weeks in the rain on the west bank of the swollen Brazos, not allowed to leave camp even for firewood because the officers were afraid their army would desert and dissolve out from under them.

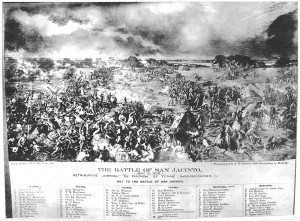

The men crossed the angry brown Rio de los Brazos de Dios on a steamboat with Houston’s vagabond army and walked in seven days through the mud from present day Raccoon Bend all the way to the battleground at San Jacinto. On the afternoon of April 21 the Mexicans were napping after a long night march and were surprised and died terrible deaths under the musket butts and knives and boot soles of the Texians. And when the Napoleon of the West was finally found and captured in a common soldier’s clothes, there was a Townsend from the Townsend Settlement among the captors, though they knew not who he was.

As Texas scrambled to build a new provisional government, the Townsend Settlement began to be referred to as the Jones Post Office Settlement because the first postmaster of the Republic of Texas lived there. The town built a house to serve as the post office with an octagonal lookout tower on top and soon the settlement was known simply as Round Top because you could see the round top of the tower from miles around.

A wave of German immigrants came next and with them a change of government as Texas was admitted to the United States. In 1851 the inhabitants of Round Top held the first of what is now the oldest annual 4th of July celebration west of the Mississippi. And then the Confederacy brought the gray days that haunted all the south and continue to do so even today. Even through the Civil War and the awful days of Reconstruction—and through the cultural tempest that followed in the wake of a broken and proud people freed—there was a since of pride and a love of that land and of the people that remained, and every year on the 4th of July they gathered to feast.

The inhabitants of Round Top incorporated and took care of one another and buried their dead under headstones and held the post-Confederacy rabble at bay and continued to gather every 4th of July in celebration of who they were and what they were and of all they had managed to build and hold on to.

The inhabitants of Round Top incorporated and took care of one another and buried their dead under headstones and held the post-Confederacy rabble at bay and continued to gather every 4th of July in celebration of who they were and what they were and of all they had managed to build and hold on to.

Such was the legacy I happened into as a participant in the Round Top 4th of July parade in 1981. We arrived early and sat on hay bales lined in three rows atop a wooden flatbed trailer pulled along behind the steady cadence of a dull green popping johnny tractor, Mr. Butch bouncing up and down on the cantilevered seat out over the trailer hitch. We wore our Little League RTC shirts and caps and tossed Bubble Yum and hard butter scotch and cinammon candies and Smarties to the people of the town and strangers alike who had come from God knows where to watch us roll by in the blue smoke behind that rattle trap tractor.

Before us in the parade line were old firetrucks and tractors and cars from many years back. There were dignitaries and important folks and people I had not and would never know. And behind us road hundreds of Fayette County residents on horseback, some of the children two and even three to a horse and the horses prancing and starting and shying from the route edges. All along the way, lining the streets and yards and the courthouse lawn, were faces sometimes five and six deep, all gathered to celebrate the birth of America.

When the parade wound up, we hopped off the Little League trailer and I watched as the Veterans of Foreign Wars marched through, their flags held high, their faces wrinkled and sweaty and rough around mostly kind eyes, their pride evident in their step and in their refusal to ride in a trailer, one old and ancient black man in front without legs being pushed in a wheel chair by an equally ancient white man behind. Most were from World War II, many were from Korea, and some were from Vietnam, and I wondered at what they must have seen and been through, and now I wonder at what they must have been trying to forget… or to make right.

I think still of those men, most of them simple boys when they went to fight for their country, for us. And I also think about the English and German settlers, and the enslaved and the freed, and the Hispanics and Jews and Move-Ins and hardscrabble survivors that shaped Round Top and made it into a place where love of God and country are a very part of the life there.

My mind also turns to the women and the children, so often neglected and abandoned in times of war, yet inherently tough if not by choice then by necessity. Somehow, underneath the party and celebration, I think there is a touch of melancholy and loss and sadness in that celebration. But there is also a sense of reunion and togetherness through thick and thin, with strangers and townsfolk alike sharing the day and the feast of brisket and sausage and beans under the shade of the oaks at the Rifle Association Hall, the polka music from the Round Top brass band carrying across the grounds and bouncing off the white walls.

There is comfort in that town… in that celebration. Comfort and life and gratitude. The best news? It still goes on today.

So if you find yourself in need of celebrating all that is good in America, make your way to Round Top this July 4th. The cannon will fire at 10 am, the pastor will give a short prayer, some politician will speak, and the parade will roll at 10:30. And while you are watching those floats and trailers and cars and fire engines and veterans and those on horseback pass by on those streets, take just a minute and look around you at the faces of your fellow citizens.

Understand that they are with you, and of you, and that they represent the very dreams of those who have come before, and of our own selves, and of those who will come later. They are Texas, and they are America, and they are absolutely beautiful.

Loving your country is not hard when you are in Round Top, not hard at all. As a matter of fact, Round Top just might give a person who has given up on this America a new appreciation for the people who have made it, and continue to make it, great.

My family and I will be there this year, standing on and cheering those kids in floats and trailers looking out at us in the crowd.

What do you say? See you there?